What is the secret to success? The answer— many of us contend— lies in the rituals and routines of  great men. By studying the biographies of billionaires and business men and adopting their habits, we believe we can attain similar success. If we read a book a week like Bill Gates, we think, we’ll found a multi-billion dollar company and be just as wealthy as him. Though this idea is obviously preposterous, something about the routines of the rich and famous still captures our imagination. One look at the most listened to podcasts on Spotify reveals our fascination with the mysterious workings of the creative process. We long to know how Beethoven prepared his morning coffee, when Picasso began his work day, when Einstein went to bed.

great men. By studying the biographies of billionaires and business men and adopting their habits, we believe we can attain similar success. If we read a book a week like Bill Gates, we think, we’ll found a multi-billion dollar company and be just as wealthy as him. Though this idea is obviously preposterous, something about the routines of the rich and famous still captures our imagination. One look at the most listened to podcasts on Spotify reveals our fascination with the mysterious workings of the creative process. We long to know how Beethoven prepared his morning coffee, when Picasso began his work day, when Einstein went to bed.

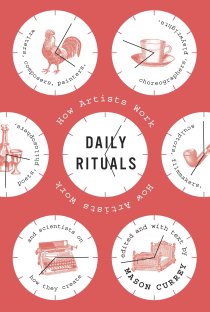

If— like me— you find such trivia endlessly entertaining, you’ll love Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: How Great Minds Make Time, Find Inspiration and Get to Work. A charming compendium of more than a 160 artists, writers, painters, poets and philosophers, Daily Rituals illuminates the many ways remarkable people throughout history have structured their days. Though there are some commonalities among those featured, no one routine is universal. Some worked for long stretches of time; others could only manage to work for an hour. Some were early birds; others were night owls. Some followed a strict schedule (Hemingway, for example, rose every morning at dawn no matter how much he drank the night before) while others were less regimented with their schedules (later in his life, man of the Jazz Age F. Scott Fitzgerald struggled to maintain a regular writing ritual). In the end, the habits of these remarkable minds are as distinctive as the people. Full of amusing anecdotes, interesting oddities and little-known facts, Daily Rituals will delight you— and perhaps reassure you that there’s no one “right” way to work. Below are 3 of my favorite authors profiled:

1. Haruki Murakami

For Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami, writing is just as much a physical challenge as a mental one. “Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity,” he told the Paris Review in 2004. To stay in peak physical condition when he’s writing, he rarely drinks, eats mostly vegetables and fish and runs (his memoir What We Talk About When We Talk About Running, of course a nod to the classic Raymond Carver story, is one of my favorite books on either writing or running). Because Murakami is a serious athlete (he began running 25 years ago and has been running daily ever since), he understands writing is a sport that requires focus and endurance. Murakami follows a strict writing schedule in much the same way he trains for marathons: he wakes up before dawn (4 am) and works for 5-6 hours. He is unwavering in his commitment. No matter how enticing the cocktail hour or glamorous the party, Murakami often declines social invitations. For him, writing is his number one priority. Lesson? Though your friends might get mad when you yet again say “no” to a night out, it’s more important to say yes to your novel and yourself.

2. Joyce Carol Oates

Is there any writer who’s as productive as Mrs. Joyce Carol Oates? One can only look upon her more than 50 novels, 36 short story collections, and countless essays and poems and gasp in wonderment. How can a mere mortal observe so much of the world and craft art from her every experience? What’s her secret?

Though Oates’s output seems impressive, it isn’t a surprise considering how many hours she spends at her desk. America’s foremost woman of letters writes every day from 8:00 to 1:00, takes a brief respite for lunch, then writes until dinner. “I write and write and write, and rewrite, and even if I retain only a single page from a full day’s work, it is a single page and these pages add up,” Oates told one interviewer. Never one to fall for the myth of mood, Oates writes no matter what; she doesn’t wait for the mercurial muse. Lesson? If you want to write, be willing to work.

3. Stephen King

Master of horror Stephen King is yet another phenomenally prolific writer. The macabre mind behind such bone-chilling books as It and The Shining has written over 62 novels and 200 short stories. His books have been adapted for the silver screen, translated into over 50 languages and sold upwards of 350 million copies. His body of work is— to say the least— intimidating.

So how has the sinister scribe managed to write so much over the course of his nearly 50 year career? First off, he writes every single day of the year. That’s right: every single day. It doesn’t matter if it’s Christmas or his son’s birthday: he sits at his desk and writes until he reaches his self-imposed quota of two thousand words. Like many in Daily Rituals, King begins writing first thing in the morning— 8:00 or 8:30— and works until he meets his goal. Some days that might be until 11:30, other days it might be until 1:00. Though he writes diligently every day, King isn’t a humorless workhorse. His schedule allows for plenty of unstructured time for rest and renewal. Once he writes two thousand words, he has the rest of the day to himself: to read, to write letters, to spend time with loved ones.