Most of us stumble through our lives in an insensible stupor, asleep to the sensory details of physical reality. We may go to the grocery store once a week but when was the last time we noticed the smell of freshly baked bread wafting through the bakery? We walk through our neighborhood almost daily yet do we see the charming old-fashioned street lamps, the lemon tree against the spring sky, the lavender and red geraniums, the tire swing and oak tree?

It’s a tragic fact of life that we become blind the more we see something. Take your significant other as an example. Perhaps when you first met your paramour, you were absolutely infatuated with her. During the giddy days of first love, your heart leapt after her every text message, sank when she didn’t call. The more you learned about her, the more you became convinced she was the long-lost half of your Platonic soul: her favorite book was Love in the Time of Cholera, her favorite singer was Otis Redding and she wanted two kids, a boy and a girl.

As you headed to her house to pick her up for your first date (a picnic in the park), your palms were so sweaty you could barely grasp the steering wheel. You arrived promptly at noon, climbed the front steps and knocked on the door. Nervous, you shifted your weight from one foot to another. “God, I hope I don’t make a fool of myself,” you thought.

When she came to the door, she instantly charmed you with her self-possession (“Hi, I’m ___,” she said so confidently, reaching out to shake your hand). You couldn’t resist her cat eye sunglasses and polka dot dress. “Nice to meet you,” you replied, momentarily forgetting how to arrange words into sentences. As you chatted over lemon rosemary tea and cucumber-rye sandwiches, you couldn’t help but fall in love with her infectious laughter, the dramatic way she told stories and made gestures with her hands. When the time arrived to take her home, you were the perfect gentleman: you walked her to her door, gave her a polite kiss on the cheek. “I had a lovely time,” you said genuinely. It was only an afternoon but you were already fantasizing about eternity.

Fast forward a year and the woman whose mere presence once made you as shy as a school boy is now your significant other. Though you once dreamed of having the opportunity to kiss her, your lips now meet with such regularity— first thing when you wake up, when you leave home for work, when you go to sleep in the same bed every evening— that the miracle is lost on you. For so long, your beloved was like a vague, chimerical dream, but after a few months of being together, it is the time before you knew her, before she was casually saying “I love you” and arranging plans for your birthday, that starts to grow chimerical and vague.

Sadly, the more familiar we become with something, the more likely we are to take it for granted. Just as we stop appreciating the object of our obsession once they become our boyfriend/girlfriend, we cease to notice things once they become commonplace parts of our day. Take the internet as an example. When the internet first made an appearance in the 1990s, we were in wonderment of the worldwide web. We marveled at its speed, the miraculous way it could connect people across continents. Now— with just the click of a button— we had all the knowledge of humanity at our fingertips.

Today, however, we are no longer in awe of the internet. Though we carry an internet-powered computer in our pockets, our phones are as astounding to us as a light switch. We’ve forgotten that a mere hundred years ago, phones could only do one thing: transmit sound. We take for granted that today they can measure our heart rate, track our circadian rhythms, take pictures and write emails.

But if we want to write, we must not lose the ability to see and be astonished by things. In her timeless classic Becoming a Writer, which I consider one of the best books ever written on writing, Dorothea Brande suggests a writer must recapture a childlike awareness of the world. Unlike adults, who very rarely inhabit the present (distracted as they are by serious obligations and mortgage payments), children only exist in this moment: they don’t dwell on the fight they had with Sally yesterday, they don’t worry about their show-and-tell presentation tomorrow. They find unbelievable joy in the smallest things: playing in a sandpit, slipping down a slide, jumping off a swing, blowing bubbles.

Children are curious creatures. Spend an afternoon with any child under the age of twelve and you’ll be tasked with solving the universe’s most mysterious riddles: why is there day and night? why is the sky blue? where did the dinosaurs go? Because they’re young, children have yet to become weary of the world: they can still be surprised by learning something they didn’t know. We adults, however, are convinced we’ve seen it all. We know there’s day and night because the earth rotates about its axis once every twenty four hours; we know the dinosaurs were wiped out by a meteor 66 million years ago. It’s hard for us to awe at a hummingbird’s incredible speed or wonder at a butterfly’s patterned wings outside our window. We marvel at Cassiopeia and cumulonimbus clouds as often as toaster ovens and cutting boards. Why? Because habit has desensitized us. As Brande writes,

“The genius keeps all his days the vividness and intensity of interest that a sensitive child feels in his expanding world. Many of us keep this responsiveness well into adolescence; very few mature men and women are fortunate enough to preserve it in their routine lives. Most of us are only intermittently aware, even in youth, and the occasions on which adults see and feel and hear with every sense alert become rarer and rarer with the passage of years. Too many of us allow ourselves to go about wrapped in our personal problems, walking blindly through our days with our attention all given to some petty matter of no particular importance…The most normal of us allow ourselves to become so insulated by habit that few things can break through our preoccupations except truly spectacular events— a catastrophe happening under our eyes, our indolent strolling blocked by a triumphal parade; it must be a matter which challenges us in spite of ourselves.”

So how do we become more mindful? Brande recommends we recover a childlike “innocence of eye”— a wide-eyed interest in the world. Rather than remain asleep to the splendor of living, more dead than alive, she suggests we set aside at least a half an hour each day to awaken our senses and simply observe. What do we see? hear? If we’re taking the subway to work, what do we notice about the people there? Where are they headed? What do they wear? If we’re stopping at our favorite cafe for a cappuccino, what do we imagine is going on with the couple in the corner? Is the woman stirring her tea in silence because she’s irritated with her husband for forgetting to do the laundry or because she’s just discovered he’s having an affair? Our goal: to treat every place as a potential setting, every incident as a potential plot line, every person as a potential character.

The greatest writers of all time were— above all— alert. Hour after hour, minute after minute, they were attuned to their experience. Turn to any page of Anais Nin’s diaries, for example, and you’ll find descriptions of accomplishment-obsessed New York and romantic, restful Paris, detailed sketches of her father, Joaquin Nin, her literary friends Truman Capote and Henry Miller, her patients, her acquaintances. Every trivial conversation contains the suspense of a Greek drama; every mundane incident a heart-racing rising action, exhilarating climax and satisfying resolution as if her life had an underlying structure as comprehensible as a novel. If we observe the world as closely, we— too— can gather a wealth of material:

“It is perfectly possible to strip yourself of your preoccupations, to refuse to allow yourself to go about wrapped in a cloak of oblivion day and night, although it is more difficult than one might think to learn to turn one’s attention outward again after years of immersion in one’s own problems…set yourself a short period each day when you will, by taking thought, recapture a childlike ‘innocence of eye.’ For half an hour each day transport yourself back to the state of wide-eyed interest that was yours at age of five. Even though you feel a little self-conscious about doing something so deliberately that was once as unnoticed as breathing, you will still find that you are able to gather stores of new material in a short time.”

If we want to be writers, we must be “strangers in our streets” and look at the world around us as if for the first time. But how, exactly, do we truly see something, especially something we’ve seen hundreds, perhaps thousands, of times? We don’t have to seek new landscapes, only fresh eyes. Like scientists who discard all their preconceptions and simply record what they see, we should remain open, receptive and attentively observe our surroundings. If we see a spring sky, what color is it? a cloud-dotted azure? an innocent robin’s egg blue? If we find ourselves in a winter landscape, is the air “chilly” or “frigid”? Are the trees “bare” or “frost-bitten”? What is the overall atmosphere and mood? Be as specific as possible. Or as Brande writes,

“You know how vividly you see a strange town or a strange country when you first enter it. The huge red buses of London, on the wrong side of the road to every American that ever saw them— soon they are as easy to dodge and ignore as the green buses of New York, and as little wonderful as the drugstore window that you pass on your way to work each day. The drugstore window, though, the streetcar that carries you to work, the crowded subway can look as strange as Xanadu if you refuse to take them for granted. As you get into your streetcar or walk along a street, tell yourself that for fifteen minutes you will notice and tell yourself about every single thing that your eyes rest on. The streetcar: what color is it outside? (Not just green or red, here, but sage or olive green, scarlet or maroon.) Where is the entrance? Has it a conductor and motorman, or a motorman-conductor in one? What colors inside, the walls, the floor, the seats, the advertising posters? How do the seats face? Who is sitting opposite you? How are your neighbors dressed, how do they stand or sit, what are they reading, or are they sound asleep? What sounds are you hearing, which smells are reaching you, how does the strap feel under your hand, or the stuff of the coat the brushes past you? After a few moments you can drop your intense awareness, but plan to resume it again when the scene changes.”

One way to sharpen our artist’s eye is to make time for adventure and novelty. Brande suggests we shake off the blinders of custom and habit and, every so often, do something new: eat pancakes for dinner, take a different route to work, go to a matinee on a Tuesday at noon.

We don’t have to venture to a lush jungle in Indonesia to see things anew. We can practice looking at things in a fresh way from the comfort of our living rooms. Stand on the coffee table. Somersault across the floor. Do a headstand. Anything to make the familiar objects of our lives as unfamiliar as possible:

“It will be worth your while to walk on strange streets, to visit exhibitions, to hunt up a movie in a strange part of town in order to give yourself the experience of fresh seeing once or twice a week. But any moment of your life can be used, and the room that you spend most of your waking hours in is as good, or better, to practice responsiveness on as a new street. Try to see your home, your family, your friends, your school or office, with the same eyes that you use away from your own daily route. There are voices you have heard so often that you forget they have a timbre of their own…the chances are that you hardly realize that your best friend has a tendency to use some words so frequently that if you were to write a sentence involving those words anyone who knew him would realize whom you were imitating.”

Dorothea Brande is a kick-in-the-pants coach who will inspire you to get to your writing table. For more tips and tricks from Becoming a Writer, read Brande on how to follow a strict writing schedule, read like a writer, and separate the creative stage of the writing process from the critical.

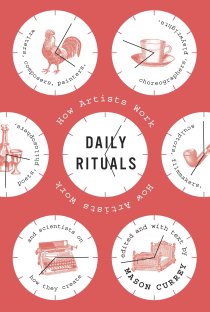

great men. By studying the biographies of billionaires and business men and adopting their habits, we believe we can attain similar success. If we read a book a week like Bill Gates, we think, we’ll found a multi-billion dollar company and be just as wealthy as him. Though this idea is obviously preposterous, something about the routines of the rich and famous still captures our imagination. One look at the most listened to podcasts on Spotify reveals our fascination with the mysterious workings of the creative process. We long to know how Beethoven prepared his morning coffee, when Picasso began his work day, when Einstein went to bed.

great men. By studying the biographies of billionaires and business men and adopting their habits, we believe we can attain similar success. If we read a book a week like Bill Gates, we think, we’ll found a multi-billion dollar company and be just as wealthy as him. Though this idea is obviously preposterous, something about the routines of the rich and famous still captures our imagination. One look at the most listened to podcasts on Spotify reveals our fascination with the mysterious workings of the creative process. We long to know how Beethoven prepared his morning coffee, when Picasso began his work day, when Einstein went to bed.

high speed internet, we demand instant gratification. The slightest delays trigger head-splitting frustration. If our friend is five minutes late for coffee or, god forbid, our web browser takes more than a split second, we feel an exasperation far out of proportion to the event.

high speed internet, we demand instant gratification. The slightest delays trigger head-splitting frustration. If our friend is five minutes late for coffee or, god forbid, our web browser takes more than a split second, we feel an exasperation far out of proportion to the event.